Background

Beginning in 2023, a number of Babylon lion staters have been circulating on the market in both auctions and dealer inventories. These staters have included types from the Alexander and Seleukos era, which are known to be two separate issues produced either side of the Babylonian War of 311-309 BC. A “hoard” of these staters was first spotted on eBay in March 2023 and subsequently other examples of the same forgeries were spotted at auction for the first time in October 2023. However, the vast majority have only appeared on the market since October 2024.

In December 2024, I published a post on the NumisForums message board outlining my brief analysis of these coins and why I believed them to be modern forgeries. More examples have since come out of the woodwork, complicating the original picture and introducing new varieties not yet seen before. This article will set out to establish why I think the coins in question are fake, the methods used to create the forgeries and obfuscate collectors, and how they relate to the original eBay “hoard” of coins spotted in 2023.

There are three arguments for declaring these coins forgeries: nonsensical die links, heavy use of hubbed dies and/or modified dies, and stylistic inconsistencies with known genuines examples. Additionally, many of the coins display other signs typical of forgeries such as unusual patinas, soft details, and odd surfaces. Before we get into why the coins are fake, I will begin with an overview of the coins so far identified as belonging to this group of forgeries.

The Coins So Far

There are 38 coins recorded for the purposes of this analysis, excluding the 50+ coins that appeared in the eBay “hoard”. 22 of these coins have appeared in auctions from various firms such as CNG, Nomos, Savoca Coins, Gerhard Hirsch Nachfolger, The New York Sale, and Solidus Numismatik. Another 12 came from a small group bought by a retail dealer, and a further 4 were sourced from other dealers.

| Type | Obverse | Reverse | # Coins | Primary Ref. | Est. Date |

| 1 | 1 | Nicolet-Pierre 4 | 328-323 BC | ||

| 2 | Δ | 4 | Nicolet-Pierre 6 | 328-323 BC | |

| 3 | Γ | 2 | Nicolet-Pierre 7 | 328-323 BC | |

| 4 | Kantharos | Γ | 2 | Nicolet-Pierre 8.5 | 328-323 BC |

| 5 | ΛΥ | 3 | Nicolet-Pierre 9.2 | 323-320 BC | |

| 6 | XO / Γ | 3 | Nicolet-Pierre 11.3 var (no M) | 320-315 BC | |

| 7 | M | XO / Γ | 2 | Nicolet-Pierre 11.3 | 320-315 BC |

| 8 | Anchor | 19 | SC 88.2a | 309-305 BC | |

| 9 | Kantharos | Anchor | 1 | Nicolet-Pierre 8.5 / SC 88.2a | |

| 10 | Anchor / Crab | 1 | SC 88.4 | 309-305 BC |

Table 1 – The types represented in this sample of forgeries. The estimated dates represent when genuine examples of the types were thought to have been minted.

Just over half of the sample is represented by Seleucid-era anchor types (Table 1), with by far the most belonging to the type published in Seleucid Coins under SC 88.2a. There’s also one further anchor type, representing SC 88.4 with a crab in the exergue, and one mule coin that combines the kantharos obverse symbol from a Nicolet-Pierre 8.5 type struck during the Alexander-era with an anchor symbol on the reverse struck during the Seleucid era.

Comprising 17 examples are the types from the Alexander-era (and early posthumous period) that are often attributed according to Nicolet-Pierre’s (NP) 1999 study. These include one example with no controls (NP 4), four with the letter Δ (NP 6), two with the letter Γ (NP 7), two with a kantharos on the obverse and Γ on the reverse (NP 8.5), three with the letters ΛΥ (NP 9.2), three more with an XO monogram above the lion and an Γ letter in the exergue (NP 11.3 var), and finally two examples that are the same as the previous but with an M on the obverse (NP 11.3).

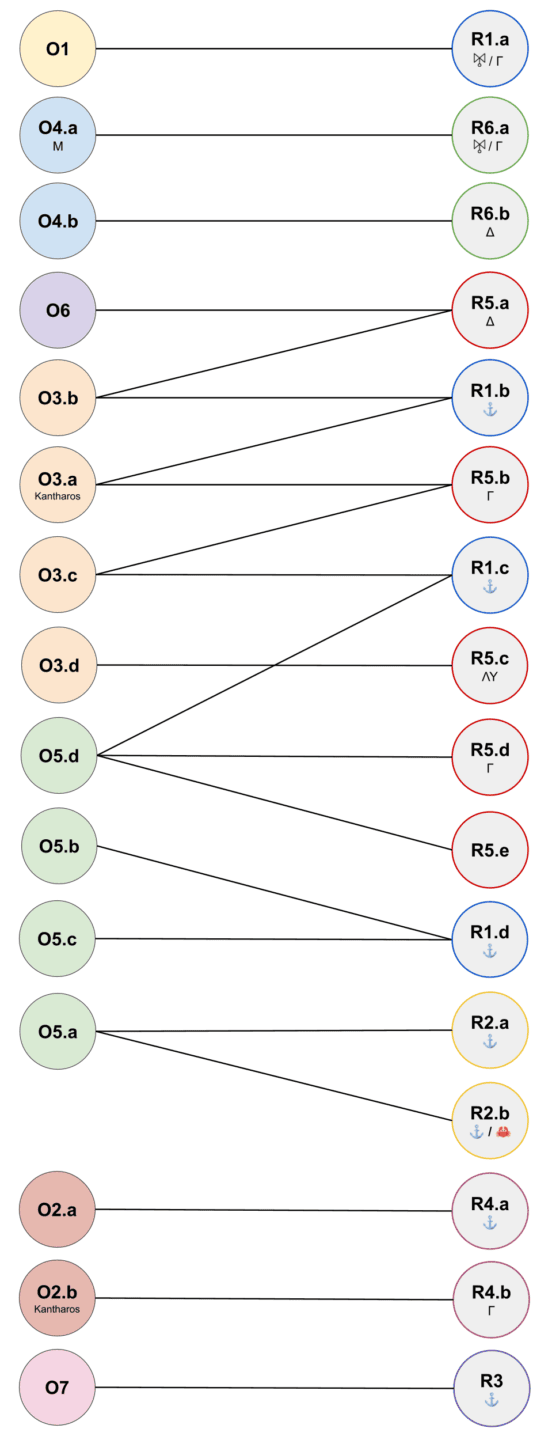

The principles of a die study were applied to these forgeries, resulting in approximately 7 obverse dies and 6 reverse dies. The number is approximate as die hubbing and/or die modification was employed for at least three of the obverse dies and four of the reverse dies. The total number of unique variant dies is 15 for the obverse and 16 for the reverse.

The numbering of the dies follows no particular order, rather the dies were roughly grouped by their stylistic traits and then numbered arbitrarily .This means that die O1 didn’t necessarily strike the first of the forgeries and it can’t be said whether die O2 precede O1 or vice versa. Similarly, the letter suffixes denoting variants of a die master, from here on referred to as a working die, are also in no particular order. The working die R5.d can’t be said to have come before or after R5.a from this analysis. The purpose was solely to group the dies and give them a unique ID to aid in analysis.

| ID | Obv | Rev | Ref. | Dies | Weight | Source | Date | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | XO / Γ | NP 11.3 var (no M) | O1 / R1.a | 16.26 | Zurqieh Vcoins #ad22162 | 02/02/2025 | Withdrawn | |

| 2 | XO / Γ | NP 11.3 var (no M) | O1 / R1.a | Dealer private purchase | 02/02/2025 | |||

| 3 | XO / Γ | NP 11.3 var (no M) | O1 / R1.a | Dealer private purchase | 02/02/2025 | |||

| 4 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O2.a / R4.a | Gorny & Mosch Auction 360 (15 Oct 2024) #256 | 15/10/2024 | Sold | ||

| 5 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O2.a / R4.a | Savoca Silver Auction 247 #118 | 15/12/2024 | Sold | ||

| 6 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O2.a / R4.a | 16.33 | Hirsch Auction 395 (11 Feb 2025) #1236 | 11/02/2025 | Withdrawn | |

| 7 | Kantharos | Γ | NP 8.5 | O2.b / R4.b | eBay listing | 18/03/2023 | Withdrawn | |

| 8 | Kantharos | Anchor | NP 8.5 / SC 88.2a | O3.a / R1.b | 16.27 | Zurqieh Vcoins #ad22163 | 02/02/2025 | Withdrawn |

| 9 | Kantharos | Γ | NP 8.5 | O3.a / R5.b | 16.17 | Hirsch Auction 395 (11 Feb 2025) #1252 | 11/02/2025 | Withdrawn |

| 10 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O3.b / R1.b | Solidus Auction 132 (21 May 2024) #1275 | 21/05/2024 | Sold | ||

| 11 | Δ | NP 6 | O3.b / R5.a | 16.47 | Hirsch Auction 395 (11 Feb 2025) #1253 | 11/02/2025 | Withdrawn | |

| 12 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O3.c / R1.c | Solidus Auction 135 (19 Sep 2024) #193 | 19/09/2024 | Sold | ||

| 13 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O3.c / R1.c | 16.43 | Hirsch Auction 395 (11 Feb 2025) #1235 | 11/02/2025 | Withdrawn | |

| 14 | Γ | NP 7 | O3.c / R5.b | Dealer private purchase | 02/02/2025 | |||

| 15 | ΛΥ | NP 9.2 | O3.d / R5.c | Savoca Herakles 1 (14 Oct 2024) #40 | 14/10/2024 | Sold | ||

| 16 | ΛΥ | NP 9.2 | O3.d / R5.c | 16.18 | New York Sale Auction 63 (16 Jan 2025) #1099 | 16/01/2025 | Withdrawn | |

| 17 | ΛΥ | NP 9.2 | O3.d / R5.c | Pars Coins Sale 50 (16 Dec 2024), #3 | 16/12/2024 | Sold | ||

| 18 | M | XO / Γ | NP 11.3 | O4.a / R6.a | 15.92 | New York Sale Auction 63 (16 Jan 2025) #1098 | 16/01/2025 | Withdrawn |

| 19 | M | XO / Γ | NP 11.3 | O4.a / R6.a | 16.48 | Hirsch Auction 395 (11 Feb 2025) #1251 | 11/02/2025 | Withdrawn |

| 20 | Δ | NP 6 | O4.b / R6.b | 16.52 | New York Sale Auction 63 (16 Jan 2025) #1101 | 16/01/2025 | Withdrawn | |

| 21 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O5.a / R2.a | 16.43 | Nomos Auction 30 (6 Nov 2023) #1373 | 06/11/2023 | Withdrawn | |

| 22 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O5.a / R2.a | Dealer private purchase | 16/01/2025 | |||

| 23 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O5.a / R2.a | 16.5 | Savoca Herakles 2 (3 March 2025) #39 | 03/03/2025 | Withdrawn | |

| 24 | Anchor / Crab | SC 88.4 | O5.a / R2.b | 15.97 | Nomos Auction 30 (6 Nov 2023) #1374 | 06/11/2023 | Withdrawn | |

| 25 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O5.b / R1.d | 16.18 | CNG Auction 548 (18 Oct 2023) #147 | 18/10/2023 | Withdrawn | |

| 26 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O5.b / R1.d | 16.45 | CNG Auction 549 (1 Nov 2023) #206 | 18/10/2023 | Withdrawn | |

| 27 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O5.c / R1.d | Gorny & Mosch Auction 360 (15 Oct 2024) #255 | 15/10/2024 | Sold | ||

| 28 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O5.c / R1.d | 16.6 | Savoca Silver Auction 247 #119 | 15/12/2024 | Withdrawn | |

| 29 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O5.d / R1.c | Private collector | 06/12/2024 | |||

| 30 | Γ | NP 7 | O5.d / R5.d | 16.61 | New York Sale Auction 63 (16 Jan 2025) #1100 | 16/01/2025 | Withdrawn | |

| 31 | NP 4 | O5.d / R5.e | Athena Numsimatics (Vcoins) #M2743 | Sold | ||||

| 32 | Δ | NP 6 | O6 / R5.a | 16.36 | Zurqieh Vcoins #ad22161 | 02/02/2025 | Withdrawn | |

| 33 | Δ | NP 6 | O6 / R5.a | Dealer private purchase | 02/02/2025 | |||

| 34 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O7 / R3 | 16.38 | Zurqieh Vcoins #ad22165 | 02/02/2025 | Withdrawn | |

| 35 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O7 / R3 | 16.18 | Zurqieh Vcoins #ad22164 | 02/02/2025 | Withdrawn | |

| 36 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O7 / R3 | Dealer private purchase | 02/02/2025 | |||

| 37 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O7 / R3 | Dealer private purchase | 02/02/2025 | |||

| 38 | Anchor | SC 88.2a | O7 / R3 | Dealer private purchase | 02/02/2025 |

Table 2 – The 38 examples of the forgeries

Seven of the coins were sold at auction and one sold by a dealer, most which were sold prior to December 2024 and before I had begun alerting some auction houses to the forgeries that were rapidly appearing in new auctions. 21 coins in total have currently been withdrawn from either auctions or dealer inventories. Four of these were withdrawn in 2023 by Nomos and CNG, the other 17 have been withdrawn since December 2024. The remaining coins are of unknown status, most were from a dealer’s inventory before it was listed for sale and the remaining coin was in a private collection.

Of examples with weights recorded, the average weight is 16.33g. This is not entirely unexpected for the series even though the lion staters were ostensibly struck on the 16.8g Babylonian double shekel standard. Figure 1 shows the distribution of average weight by type for lion staters where the green diamonds are Alexander-era types and the blue belong to the Seleucid-era. Notably, the average weight of the Alexander era types are almost all between 16-17g, while except for the anchor-on-haunch types the Seleucid era averages are all well below 16g.

The sample used for this distribution comprises approximately 470 Alexander-era examples with an average weight of 16.54g and 90 from the Seleucid-era with an average weight of 15.95g. There are 46 examples representing the type SC 88.2a alone, which is the same type as all but one of the Seleucid-era forgeries documented here. Only six (13%) of the 46 genuine coins have a weight of 16.3g or more and a further four weigh between 16.1 and 16.3g, meaning 37 (79%) are below 16.1g in weight with the majority of these below 16g.

Figure 1 – Distribution of average weights by type for Alexander-era (green) and Seleucid-era (blue) lion staters. Data points in grey are where fewer than 3 examples were available.

When looking at the average weights for the forgeries, and splitting by Alexander and Seleucid-era types, we get an average of 16.33g for the Alexander types and 16.34g for the Seleucid types. None of the SC 88.2a forgeries with weights listed are below 16.1g, the lightest is 16.18g. This clearly shows that these forgeries were struck on the same weight standard without regard for the slightly different weights expected of Alexander versus Seleucid types. It could be argued that genuine lion staters are typically quite worn and the sample that comprises the forgeries are relatively unworn but that would mean the Alexander-era forgeries would be expected to weigh closer to 16.8g than the 16.33g they currently average. The reasonable conclusion is that the forgers were unaware of the subtle different in weights or simply did not care.

Die Links

When viewed as a whole, an immediate problem becomes apparent with this group of 38 forgeries: die linkages between Alexander-era and Seleucid-era types. Over the past 2 years I’ve been compiling a corpus of mostly Alexander-era lion stater types for the purposes of a die study and an update to Nicolet-Pierre’s classification of the series. To date I’ve identified just over 470 unique examples of these types, which were struck by approximately 200 obverse dies and 300 reverse dies. Additionally, I’ve recorded another 100 examples of the Seleucid-era type (e.g. those with an anchor above the lion). I’ve yet to come across a single die link between the Alexander types and the Seleucid types. To my knowledge, those who have studied this coinage before me, such as George Hill, Edward Newell, Martin Price, and Hélène Nicolet-Pierre, have also failed to discover any links between these two series. For all intents and purposes, they are separate from one another and are often studied this way.

The types most likely to share a link with the earlier Alexander series are SC 88.1a and SC 88.1b, which I have studied briefly in my article The Birthmark Anchor Coins of Seleukos I Nikator. These types are the earliest to be struck in the Anchor series and as evident in Figure 1, also have a significantly higher average weight – on par with the previous series of coins. Additionally, there is also one obverse die that depicts Ba’al with uncrossed legs, which is a characteristic only found in the prior series. However, no die links between these types and the earlier Alexander-era types have been found by myself or others and there are significant differences in the style of both Ba’al and the lion that points to a clear break between the two series.

There are four obverse dies identified among the forgeries that pair with both an Alexander-era and Seleucid-era reverse type. Three of these are working dies of the O3 master die and the fourth is a working die belonging to the O5 master (Fig. 2). The obverse die O3.b is linked to R5.a with a delta symbol (Nicolet-Pierre 6) and R1.b with an anchor symbol (SC 88.2a). Obverse die O3.a is also linked to R1.b with an anchor and R5.b with a gamma (Nicolet-Pierre 8.3). Die O3.c is then linked to R5.b with a gamma and R1.c with an anchor. Lastly, die O5.d is linked to R1.c with an anchor, R5.d with a gamma (Nicolet-Pierre 7), and R5.e with no control symbol (Nicolet-Pierre 4).

Moreover, the above links do not include the other working dies which are connected via having been created by the same master die. For instance, O3.d, which is used for many of the Seleucid-era types, is paired with a ΛΥ reverse type (Nicolet-Pierre 9.2) but is equally problematic where it concerns the authenticity of these coins since we wouldn’t expect a die hub to have been used across two entirely different series where no genuine die links are known. Master die O2 is also connected via its working dies to an anchor type (SC 88.2a) and a gamma type (NP 8.3), with the strange addition of having a kantharos on the latter type’s obverse but not the former. It’s unlikely the kantharos was engraved in positive on the die hub, meaning it was likely added to one of the working dies in negative after being struck from the master, resulting in two working dies where only one has the kantharos.

Figure 2 – Die links between the different obverse and reverse working dies. Presented in no particular order.

The kantharos obverse symbol is only known to the Alexander-era type Nicolet-Pierre 8.3, it has never been found on any Seleucid-era types, nor has any of the other obverse symbols from the NP 8 group of types. On its own, this evidence would typically be enough to condemn these coins as outright forgeries. These die links do not exist in the extensive corpus of examples we have from these series, nor would we expect them to. To explain away this problem caused by the kantharos, one has to argue that either die hubbing was used in ancient times and the O2 master was kept for 15 years or more to strike working dies from both series, or that the original die was kept for 15+ years and re-cut to remove the kantharos symbol before striking the Seleucid-era type. Both arguments would be a stretch of logical reasoning, particularly as it is still debated whether hubbing was ever used during ancient times. We also have an example in O3.a that has a kantharos symbol on the obverse and was used to strike both Alexander-era and Seleucid-era types. One would then need to argue that these series were struck simultaneously.

The last Alexander-era type represented in this sample to be minted is Nicolet-Pierre 9.2, which is dated to circa 323-320 BC based on its association with the Alexander tetradrachm types Price 3689 and Price P181 that were thought to have been minted shortly after Alexander’s death in 323 BC. The absolute earliest possible dates for the anchor types mentioned above, SC 88.2a, would be 311 BC but more likely after 309 BC given Demetrios soon captured Babylon again from Seleukos I in 310 BC. It seems most likely that the anchor-on-haunch types were then struck first and best estimates would suggest a date no later than 308 BC for those. This would mean SC 88.2a would’ve been struck approximately 15 years after Nicolet-Pierre 9.2, circa 309-305 BC. If there was ever to be a die match between the Alexander-era and Seleucid-era types, it would be from one of the types at the end of Nicolet-Pierre’s series (e.g. NP 15-19) that were possibly struck during Antigonos’ rule of Babylon and not a type struck 15 years earlier, before Seleukos’ first satrapy of Babylon.

There are also problematic die linkages within the examples representing the Alexander-era types. For example, the working dies of O4 were used to strike examples of Nicolet-Pierre 11.3 (R6.a) and Nicolet-Pierre 6 (R6.b). The latter type is believed to have been minted during Alexander’s lifetime, perhaps circa 325-323 BC, based on a stylistic analysis. The former type, NP 11.3, was minted sometime between 323-317 BC, and a date after 320 BC seems most probable. While there is not a large gap in terms of time between these types, there are numerous other types that fit in-between these two, including the two largest issues struck throughout the entire series: NP 7 and NP 8. These two types account for nearly 25% of the 470 examples I have recorded.

Moreover, the die linkages I have documented among these types does not support a hypothesis that would have a die hub being used to produce a working die for NP 6 and then NP 11.3. Starting with NP 6, it is linked by obverse dies to examples from NP 4 (no control) and NP 7 (gamma). A reverse from NP 8.8 is then die linked to a reverse of NP 7. Nicolet-Pierre 9.3 then has an obverse die link to NP 11.8 and a reverse die link to NP 11.7. Furthermore, an unpublished type of NP 9 with three dots formed in a triangle on the obverse has an obverse die link to NP 10. We have a clear pattern of sequential types being die linked to the types immediately preceding and succeeding them. The only “jump” we see is NP 9.3 to NP 11.7 but the NP 10 issue was a small one so this is not surprising. A die link between NP 6 and NP 11.3, however, would be surprising and entirely unprecedented in the Alexander-era series of types.

These die links are strong evidence that the coins at question in this article are forgeries. Among my sample of 470 Alexander-era examples and 100 Seleucid-era examples, no die links between the two series are known. Additionally, the die links within the Alexander series follow a very typical sequential pattern that suggests one type was minted at a time and when the next type was introduced some old dies from the previous type may have continued to have been used. Furthermore, there is no evidence of die hubbing among these genuine examples and I have seen no evidence of die linkages bridging disparate types separated in this series by both time and sizeable outputs.

Die Hubbing

The practice of die hubbing in ancient times is still debated (Fischer-Bossert & Stannard, 2011) so the presence of it in this sample of coins may not be enough to declare the coins as forgeries outright. However, like with the nonsensical die links established earlier, there is strong evidence that working dies of types from both the Alexander and Seleucid series originated from the same master die. This would require that the master be cut in the mid 320s BC, used to create one or more working dies, and then retired for a period of 15 years or more before being put back to work to create working dies for a different series.

If there were known die links between these series, or even evidence of die hubbing being used at all in either series, then the hubbing in this sample of forgeries may not seem so preposterous. As with the die linkages, there is no evidence for die hubbing being used at any point in the minting of the Babylon lion staters, whether during the Alexander series or later Seleucid series. To reiterate, I’ve identified over 200 obverse dies and 300 reverse dies from Alexander series types and have not yet come across one example of die hubbing.

The closest we see to this are possible re-engravings of dies such as that seen in one example of Nicolet-Pierre 7 (Price, 1973). In that instance, the delta control symbol belonging to a die used to strike Nicolet-Pierre 6 examples was recut and engraved over by a gamma symbol to strike Nicolet-Pierre 7 types. One would imagine that had they been using die hubs, this wouldn’t be necessary as the control symbol would be left off the master die and engraved specifically for the individual working dies. It’s also notable that the recutting was difficult for them to hide entirely, or that they did not care enough to completely hide it.

The tables below (Table 2 and 3) outline the characteristics of each die that can be used to discern the master dies from each other and the working dies from the master die. There are some indications that demonstrate die hubbing was used for at least some of these dies, rather than a more typical practice for ancient die sinkers of re-engraving an existing die to enhance details or alter control symbols.

| Die | Controls | # Coins | Notes |

| O1 |

3 |

|

|

| O2.a |

3 |

|

|

| O2.b | Kantharos |

1 |

Same as O2.a, except

|

| O3.a | Kantharos |

2 |

|

| O3.b |

2 |

Same as O3.a, except

|

|

| O3.c |

3 |

Same as O3.b, except

|

|

| O3.d |

3 |

Same as O3.c, except

|

|

| O4.a | M |

2 |

|

| O4.b |

1 |

Same as O4.a, except

|

|

| O5.a |

4 |

|

|

| O5.b |

2 |

Same as O5.a, except

|

|

| O5.c |

2 |

Same as O5.b, except

|

|

| O5.d |

3 |

Same as O5.C, except

|

|

| O6 |

2 |

|

|

| O7 |

5 |

|

Table 3 – List of discriminators used for obverse die identification

One example of this can be found in the O5 series of working dies. It’s not clear which variety is the most like the original master as the changes do not follow a sequential pattern and an analysis of die wear does not point to an obvious contender either. The most notable difference between O5.a and O5.b to O5.d is the length of Zeus’ staff between his right arm and right leg. In O5.a this distance is relatively small and contains approximately 3 “dots” of the staff, while in the other dies, the angle and position of the staff has changed allowing for 4 or 5 “dots” to be placed between arm and leg.

Figure 3 – Working die variations of the O5 master die.

Similarly, the bottom of Zeus’s right leg is depicted with cloth folds in a vertical alignment on O5.a and O5.b, while on O5.c and O5.d these folds transition to a slightly angled and then diagonal alignment. While it could be said this may have been necessary due to die wear, as examples of O5.b have considerably softer details than those of O5.a, examples of O5.c are quite sharp and do not show the same softness in the details. It seems unlikely that the details were improved by recutting the die given the similarity of the rest of the die to O5.a. It would only be possible if this feature did not exist in the master die and was instead left for engraving in the working die. We also know that O5.a was paired with a Seleucid-era reverse type while O5.d was paired with both Alexander-era and Seleucid-era types, suggesting that if these were genuine coins the first variant of the die would be O5.d and that O5.d had been retained in its current state for more than a decade for it to be around when the striking of the Seleucid types occurred.

We can also demonstrate that there was not a sequence of die modification in the reverse order. This is because the O5.d variety has some more robust features not present on O5.a, such as the size of the mouldings on the throne legs and Zeus’s hair behind the head. Since these would be engraved in negative, they can’t be easily filled in on a normal die. Additionally, it would be difficult to cover the traces of moving the staff and changing the size and shape of the lower right leg. It would, however, be possible to make these changes using hubbing, as the more robust features could be thinned from the master die while working in positive.

| Die | Controls | # Coins | Notes |

| R1.a | XO / Γ | 3 |

|

| R1.b | Anchor | 2 |

Same as R1.a, except

|

| R1.c | Anchor | 3 |

Same as R1.b, except

|

| R1.d | Anchor | 4 |

Same as R1.c, except

|

| R2.a | Anchor | 3 |

|

| R2.b | Anchor / Crab | 1 |

Same as R2.a, except

|

| R3 | Anchor | 5 |

|

| R4.a | Anchor | 3 |

|

| R4.b | Γ | 1 |

Same as R4.a, except

|

| R5.a | Δ | 3 |

|

| R5.b | Γ | 2 |

Same as R5.a, except

|

| R5.c | ΛΥ | 3 |

Same as R5.b, except

|

| R5.d | Γ | 1 |

Same as R5.c, except

|

| R5.e | 1 |

Same as R5.d, except

|

|

| R6.a | XO / Γ | 2 |

|

| R6.b | Δ | 1 |

Same as R6.a, except

|

Table 4 – List of discriminators used for reverse die identification

Another example, this time from the reverse dies, is the R1 master die. Of the four working dies, three use the Seleucid-era anchor symbol and just one (R1.a) an Alexander-era monogram and gamma from type Nicolet-Pierre 11.3. As has already been discussed, this linkage between Alexander and Seleucid types would likely be sufficient to declare the coins forgeries but a closer analysis will also help support the hubbing hypothesis over a recut dies argument.

The first working die, R1.a, is linked to only a single obverse (O1) that is not used for any other coins in this sample. The reverses struck from R1.a are the freshest of the R1 group and are the strongest candidates to support a repaired/recut die counter-argument given the increasing wear in the subsequent working dies. In the next die, R1.b, the details are already considerably softer and the control symbols have been entirely replaced, without a hint of their existence, by a large anchor above the lion (Fig. 4).

Figure 4 – Working die variations of the R6 master die.

R1.c continues with the anchor control symbol but introduces a change to the lion’s tail, removing a “crook” that existed on the previous two types. One would find it hard to imagine an argument for this in the recut die scenario given the effort it would take to cover up the previous tail and engrave a new one. It’s also evident that the new tail hasn’t simply consumed the area occupied by the previous tail, which would be the easiest way to mask the repairing effort by simply enlarging the negative space. However, under a hubbing scenario, the tail need not be engraved on the master die so alterations within the working dies would be relatively simple.

In the final die of the R1 group, R1.d introduces changes to the lion’s mane. These are not minor changes but involve restyling the tufts of fur on the chest, neck, and behind the head. The new mane is of finer detail in parts and would require building back small areas of the die previously cut into negative. The anchor has also lost one of its toroidal mouldings on the shaft, a further modification that would require filling in negative space in the die under a repaired die hypothesis.

Perhaps most damning of all, however, are the die linkages that would have the recut die used to strike Alexander-era and Seleucid-era types simultaneously (Fig. 5). R1.b, an anchor type, is linked to O3.b, which was used to also strike an Alexander-era type with a delta symbol (Nicolet-Pierre 6). Furthermore, R1.b is linked to O3.a, a type with a kantharos on the obverse that was also used to strike an Alexander-era type with a gamma symbol (Nicolet-Pierre 7). This reverse die, R5.b, is then linked to an obverse (O3.c) also used to strike both Alexander and Seleucid-era types (R1.c).

This would require that at least three Alexander-era obverse dies were kept around to strike Seleucid-era types. However, this becomes impossible when one realises these dies would have had to have been reverted to their earlier die state when striking some of the Seleucid-era types under a repaired die scenario. This is because O3.a, with a kantharos on the obverse, was used to produce one Alexander-era (R5.b) and one Seleucid-era type (R1.b) but the kantharos is not present on the subsequent versions of this die that was also used to strike both Alexander-era and Seleucid-era types. It’s simply an impossibility to believe not only that these dies were recut so drastically and nonsensically throughout their lifetime but also that the engravers reverted the dies to their original state to strike O3.a/R1.b and then removed the kantharos yet again to strike O3.c/R1.c.

Figure 5 – An impossible combination. Obverse dies O3.a (top) and O3.b (bottom) both struck Alexander-era and Seleucid-era types in their respective states (top-left clockwise: R5.b, R1.b, R1.b, R5.a). This would only be compatible with a “recut die” hypothesis if these three types (NP 6, NP 8.3, and SC 88.2a) were struck simultaneously, which we know is not the case.

Numerous other such examples exist among this sample that not only strongly suggest forgery but essentially prove it. The only way these changes to the dies could have been made is by using some form of hubbing or otherwise counterfeiting of the dies (e.g. transfer dies). In-conjunction with the evidence from the nonsensical die linkages, many of the examples can safely be declared forgeries. However, there exist a handful of examples with no odd die links or variations to a die, such as O1, O7, and R3. To further demonstrate that examples struck from these dies also belong in this series of fakes, we can also look to stylistic evidence.

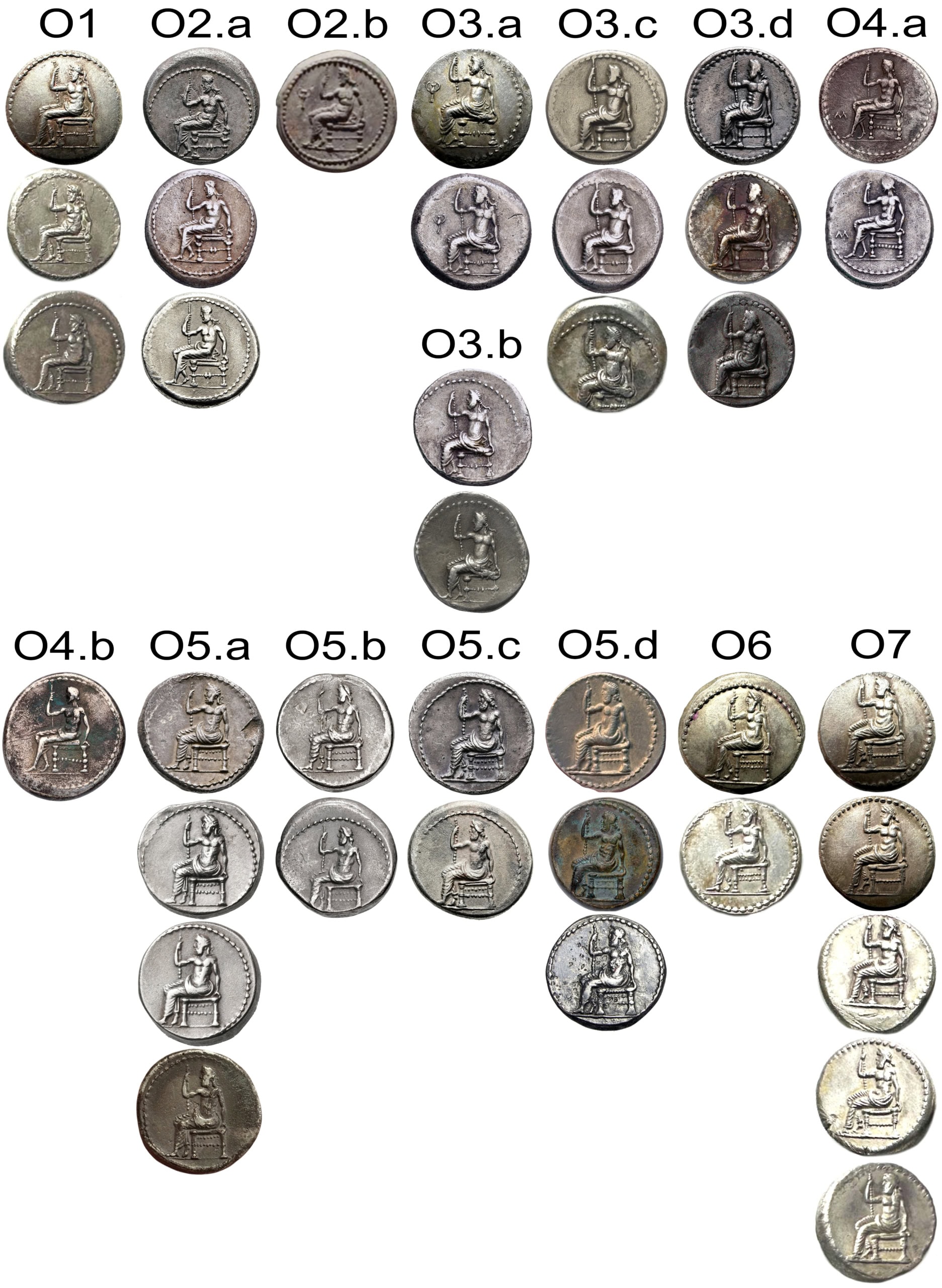

On the basis of style

Making determinations of authenticity based on style can always be difficult due to the subjective nature of art – how does one adequately describe a style so that it can be understood by another? For the following analysis I will try to stick to quantifiable aspects of style: the size, shape, count, or presence of characteristics. One of the first that stood out to me when viewing these coins for the first time was the number of obverse dies with two cross-struts between the legs of Zeus’ throne. From my own research into the Alexander-era and anchor-on-haunch types, I’ve come to learn that this is very much a feature of the Seleucid-era types. It’s not just rare to see in the Alexander-era types but incredibly rare.

Referring again to the approximately 470 examples of Alexander-era coins I’ve documented, I’ve found only six examples that feature a double cross-strut on the reverse throne. All six are from the same type, Nicolet-Pierre 19, which is the last type Nicolet-Pierre places in her sequence of the Alexander-era types. I also agree with its placement in this order; if it’s not the last type in the sequence it’s certainly one of the last types and likely dates to after 317 BC. Yet in the sample of forgeries being studied here, we see four master dies and half of the total working dies featuring double cross-struts (O4, O5, O6, O7). Of these master dies, only O7 was not used to strike an Alexander-era type. Six of the 18 Alexander-era coins feature this characteristic, a ratio magnitudes higher than we would expect to see. Not to mention that not one of these types being imitated, namely NP 4, 6, 7, 8.5, 9.2, and 11.3, have any known genuine examples with double cross-struts.

Another unusual stylistic aspect is found on the reverse dies R6.a and R6.b where the lion has tilted its head upwards towards the sky (Fig. 7). This is a feature I’ve yet to find on any other example of NP 6 or NP 11.3, let alone any other Alexander-era die. While some dies may depict the lion with a slight tilt to its head that puts its gaze above the horizon, none depict the lion with a howl-like head position.

It’s also interesting to see that the tail on R6.a and R6.b is different: on the former it curves around behind the lion and down between its legs, on the latter it forms a U shape behind the lion. The U shape is typical of the earlier Alexander-era types, specifically those from the Mazaios staters up until the type depicted in R6.b (Nicolet-Pierre 6). After NP 6, the tail doesn’t return to this shape and typically adopts some form of shape that takes it between the lion’s legs, as we see on R6.a. It seems to me odd, if we are to believe that R6.a is merely a re-cut version of R6.b, that the engravers would bother to update the tail style to match what is expected for the type being minted at that time. This would be a trick that forgers have motivation to employ to help blend their dies with the expected styles of the type but I can’t see the motivation for the Babylonian engravers to employ the same fix when recutting a used die.

Figure 7 – Changes to the type of lion tail used on two different working dies from the same master die.

It’s not clear where the forgers got their inspiration for R6 from, given I’ve yet to come across a similar example in my extensive searches, but it is clear where they got the inspiration, if not the die itself, for one of their other forgeries. In my corpus of Alexander-era types I came across two examples, sharing the same obverse and reverse die, that had extremely similar features to the master dies O2 and R4 (Fig. 8). They share a similar angle and spacing of Zeus’s right arm relative to the leg, they have a similar bend in the left arm that rests on the throne, the squiggle of cloth behind Zeus’s lower back is of the same form, and most notably of all, they have cross-struts with two dots in the middle that are slightly larger than the others. Both of these examples are of the type NP 8.3, suggesting the forgers may have started with the kantharos on their die and removed it in subsequent iterations. Likewise, the reverse featured a gamma to begin with and then was likely replaced with an anchor.

The genuine examples line up closest with O2.b, the variant with the kantharos, as besides the kantharos it also has the cross-strut dots of a similar size to the genuine examples. Similarly, the reverse of the genuine examples line up best with R4.b, the variant that is paired with O2.b and features the gamma control symbol rather than anchor. It’s difficult to say whether one of the two genuine examples served as the transfer die for the forgeries or if a similar example of the same dies was available to them. The forgers did appear to make some modifications after transferring the die, however.

The right arm of Zeus is more rounded at the elbow in the forgeries, pushing the forearm slightly further away from the staff. The genuine examples also have Zeus with two hair strands falling onto his left shoulder while the forgeries just have the one. The mouldings of the throne leg have been exaggerated, to a degree that has no parallel among genuine examples in my corpus. Finally, the two dots in the middle of the cross-strut have been significantly enlarged. It’s unclear whether the forgers thought these were signs of a die break and intended to enlarge them to show a progression in the break or if they mistook them for aesthetic features of the cross-strut. It’s also possible they decided to enhance them simply to introduce eye-catching, but insignificant, differences to throw off numismatists and collectors searching for the parent dies. Such a modification would line up with the observations of Fischer-Bossert & Stannard (2011), namely that forgers would attempt to “modify [the dies] to hide the individualities of the model” and “to substantially alter elements of the image, in order to make a ‘new die’”.

Figure 8 – The dies O2/R4 in the forgery (top) likely come from a genuine example with the same die pair as these bottom two coins. Source: Roma Numismatics Ltd

Auction XXVII, lot 357 (middle); CNG Triton XXV, lot 512 (bottom).

The lion from R4.a and R4.b also appears to be derived from the die of the genuine examples. There are some minor differences here, too. The paws of the lion curve upwards along their length and are also curved at the back. The ears of the lion have been exaggerated and now stick up above the head and mane. The toes of the paws are smaller in size, resulting in flatter paws. A groove running along the belly of the lion is no longer apparent. Muscle or some other detail has been added to the shoulder area and crudely enhanced in places. In general, there’s a tendency by the forgers towards enlarging features and reducing some of the finer detail and style to cruder imitations. Apart from the issues with die linkages and the fabric of these forgeries, the crudeness of style is an immediate and obvious indicator of their forged nature.

In addition to the inconsistency with the usage of two cross-struts between the throne legs, there are various other stylistic indicators that do not match what we would expect of a Alexander-era, or Seleucid-era, type. When it comes to the reverse dies, reverses R1 through R3 have a distinctly Seleucid-era style to them, yet dies belonging to R1 have been used to strike both Alexander and Seleucid era types in this sample. The clearest stylistic giveaway is the lion’s muzzle, i.e. its nose and mouth. For the earlier Alexander-era types, there is wide variation in how the lion’s muzzle is depicted but it is generally fiercer, more determined-looking with its head often bowed, and more expertly engraved with realistic proportions. This compared to the Seleucid-era lion that can often have a teddy bear appearance with an overly large muzzle, softer features, and a less threatening pose.

Genuine examples of the SC 88.2a type (Fig. 8, middle row) are the closest in style to the lions we see on the forged dies R1 through R3. Genuine examples of lions from Alexander-era types imitated by the forgeries are far different to the lions on these dies. However, the fierceness and determined look is captured in the lion from R4 (Fig. 8) but as we know this die likely was inspired or copied from an Alexander-era die, even though it was subsequently used to produced three Seleucid-era forgeries and, so far, only one from the Alexander era. The remaining three reverse dies from the forgeries in Fig. 8 (bottom row) all depict the “teddy appear” style lion characteristic of the Seleucid-era types, yet R1.a was used to strike an Alexander-era type.

Figure 9 – Top row: genuine examples of Alexander-era reverse types depicting lions with somewhat fierce expressions, slightly bowed heads, and a high level of artistry. Middle row: genuine examples of Seleucid-era reverses of the type SC 88.2a, showing the more “teddy bear” like appearance of the lion, emphasised by the larger muzzle, softer expression, and cruder features. Bottom row: examples of reverses from the forgeries studied here. The first three examples from the bottom row depict a lion more similar to the Seleucid-era style, while the fourth example is known to have come from an Alexander-era type yet was used by the forgers to strike a Seleucid-era type.

In addition to the die links between Alexander-era and Seleucid-era types, the discovery of the parent die for one of the forgeries and the stylistic changes the forgers introduced is one of the strongest and most damning pieces of evidence that condemns this group of coins. Moreover, the engravers predominantly relied on Seleucid-era lion styles for the reverse types even when striking Alexander-era types but they also did the opposite, using an Alexander-era styled lion for Seleucid-era reverse types. While the forgers had some semblance of what they were doing, they did not appear to pay enough attention to the details or to care enough, and thus the coins are readily condemned.

On the topic of mistakes, there is one final mistake worth pointing out. As discussed, the forgers modified the tail style for the type to try and match genuine examples they were probably familiar with. This included making the tail for the NP 6 extend out behind the lion in a U shape but for the other types, such as NP 7 and NP 9.2, they had the tail loop up behind the lion and then cross between its legs. We can see evidence of just how the forgers made these changes (Fig. 10). In examples of R5.a in particular, we can clearly see the tail’s body extend over the top of the lion’s haunch. It’s difficult to see how a real die sinker would make this mistake as the tail is a shallow feature that would only require engraving slightly into the top of the die’s surface but for this feature to be made the engraver would need to continue engraving the tail down into the negative space cut away for the lion’s haunches.

This would be an easier mistake to for a forger using die hubbing with a transfer die. The original die would be copied from an existing example or engraved in positive. If the latter, the original tail would be cut away while in positive since it would be easy to level it with the surface while working in positive and allow the working dies struck from the master to adopt any tail style needed. When these working dies were created from the master, the forgers would add the tail design in. Perhaps they made a mistake in their interpretation of negative space and thought to engrave a convincing tail it needed to blend in gradually with the back of the lion. To do this, they continued the tail line down into the negative space used to create the lion’s haunches and produced a completely unbelievable design where the tail looks “tacked on” to the back of the lion.

Figure 10 – Examples of R5.a and R5.b where the tail sits above the haunches of the lion, indicating modification in negative by the forgers. The flaw is gradually reduced in the examples of R5.b

The eBay “Hoard”

The first time I was made aware of these forgeries, and to my knowledge the first time they appeared on the market, was in an eBay listing titled “Lot of 56,Babylonia, Tetradrachm, 328-323 BC, Babylon”. The seller included two photos of the 56 coins grouped together (Fig. 11, Fig. 12), one of their obverses and one of their reverses. Immediately it was apparent to me that the coins were forgeries for two reasons: the use of the same obverses for Alexander-era and Seleucid-era types and that the lions on types from these different eras were seemingly identical. Although the photos are not of very high resolution, it is still possible to make these determinations with a reasonable degree of confidence. I decided to contact the seller to make them aware that the coins they were selling were forgeries and they soon sent me additional photos of the group.

Figure 11 – Obverses of the 56 coins from the eBay sale

Figure 12 – Reverses of the 56 coins from the eBay sale

Just one coin from this “hoard” of 56 is included in the sample analysed here (coin #7). That is because the seller sent me a small group shot of 3 coins (Fig. 13) from the 56 to see if having a better look at the coins would assuage my suspicions. This photo only further confirmed my suspicions. We see examples of reverse die R4 paired with the O2 master die, both demonstrating the hubbing process used to create these forgeries as well as the mistake in mixing Alexander-era and Seleucid-era types.

Figure 13 – Three examples from the larger group of 56 in the eBay “hoard”. The bottom example is coin #7 in this article.

The vast majority of reverse dies in this hoard come from the same R4 die seen in the above group of 3 coins. Figure 14 below highlights the coins according to their reverse die with purple being R4 and green R6, of which there are 35 R4 reverses and four R6 reverses. Of these 35 R4 reverses, nine have no control symbols and three have the gamma control (R4.b). Those with no control symbol haven’t appeared at auction or otherwise were made available to me and haven’t been included in the sample studied here but we can tentatively assign them as reverse die R4.c. The four R6 reverses comprise three examples with the delta symbol (R6.b) and just one of the XO monogram / gamma type (R6.a).

Figure 14 – Master dies identified by different colours. Purple identifies the R4 die and green identifies R6. The non-circled coins are of an unknown master die.

The same could be repeated for the obverse dies but the image quality is slightly worse and the obverse dies are much harder to differentiate from one another without clearer photos. We can say that there appears to be examples of O1, O2.a, and O2.b. There may also be an unknown variation that is similar to O2.a but with the drapery hanging off the side of the seat like we see in O3, and we can be sure it’s not O3 itself due to the gap and angle between the right arm and leg of Zeus.

Aside from the nonsensical die linkages, significant use of die hubbing, and stylistic inconsistencies, there are also other signs that these 56 coins (and the 38 studied in this article) are forgeries. This “hoard” photo shows just how similar many of these coins are in centering, preservation, and flan shape. Genuine lion staters typically are not well centered with either parts of Zeus or the lion commonly being partly off-flan. Most of the examples in the eBay hoard are well-centred, to the degree that much of their dotted border remains on-flan.

They’re also of a similar level of wear and die state, showing no signs of the significant die wear that many lion staters are found in. It could be argued that we’d expect coins from a hoard to be similar to one another and of similar die state but given that it’s certain the dies were at least re-cut (though I have disproved this hypothesis earlier), it is not credible that they would all be found in the same die state. It would require that some examples be struck from the die when it was relatively fresh, the die then wore out and was re-cut, and then the other examples were stuck and only combined together with the previous examples that had been struck from the original die in its fresh state.

There is one more aspect to this eBay hoard that is worth discussing: the genuine examples. After I contacted the seller alerting them to the forgeries, they sent me additional photos of a smaller group of 23 coins containing both Alexander-era and Seleucid-era types (Fig. 15). What struck me first when I saw these coins was that they appeared much more convincing than the earlier group and were possibly genuine. We see the hallmarks of a genuine hoard: thick dark patinas, crusty deposits, misshapen flans, varied die states and wear, signs of use such as test cuts, and a varied group of types. Notably, not one of these coins shares a die with the other 56. The two Alexander-era types, those with the Mazaios legend on the reverse above the lion, also matched known dies for those types. Some of the Seleucid-era types were easily matched to known genuine dies as well.

Figure 15 – A second group of 23 coins, likely genuine, which the eBay seller shared with me and indicated were being sold by the same source and supposedly came from the same hoard.

It appears that the person supplying the eBay seller with the coins may have attempted to legitimise the group of 56 by claiming it was with this group of 23 genuine coins. This is a common tactic, though one that can backfire and easily make the forgeries stick out like a sore thumb when compared next to the real deal. From what I understood, the eBay seller had not purchased these 23 coins, instead opting for the group of 56. While I do not know what happened to the group of 56 coins, the second group of 23 soon found its way to the auction market.

Beginning in November 2023, Heritage Auctions in the US began including coins from this group in their weekly auctions. Over a period of 8-9 months, all of these examples were sold by Heritage and can be found in auction records online. Given that Heritage Auctions has NGC encapsulate and grade their coins, and that NGC rejects coins for encapsulation that it does not believe to be authentic, we have even more reason to believe this group of 23 is entirely genuine. 21 of these coins can be found here:

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232347, lot 64061

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232350, lot 62072

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232351, lot 63084

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232402, lot 62021

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232403, lot 63013

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232404, lot 64076

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232405, lot 61074

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232410, lot 61068

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232412, lot 63105

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232414, lot 61094

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232416, lot 63095

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232417, lot 64086

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232419, lot 62067

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232420, lot 63066

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232420, lot 63067

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232422, lot 65093

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232424, lot 62078

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232425, lot 63097

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232428, lot 62068

Heritage Auctions, Auction 232431, lot 61076

Heritage Auctions, Auction 3111, lot 36034

Conclusion

For experienced numismatists familiar with the Babylonian lion stater coinage, this article is hardly necessary to discern the authenticity of these pieces. There are many things wrong with these coins, most of which would outright condemn the coins on their own. Additionally, they show all the hallmarks of a new group of forgeries being dispersed on the market across multiple auction houses and dealers without verifiable provenance and all with similar patina. The most conclusive evidence, of course, are the die links. Unless we are to rewrite all we know about both the Alexander-era and Seleucid-era lion staters, not to mention Alexander’s other coinage at Babylon, these coins are simply an impossibility that would require a large portion of this coinage to be struck simultaneously. We know this is not the case from die studies, from hoard evidence, from stylistic analyses, and from comparisons with other coinage – such as the anchor tetradrachms Seleukos I also struck during the same 311-305 BC period.

I believe I’ve also demonstrated that die hubbing was utilised in their forging, and that arguing that the dies may have just been recut in ancient times is not feasible. A likely candidate for the parent die of one of the forgery master dies was discovered and the differences introduced by the forgers not only prove that the dies were modified but also that they were likely modified so as to help camouflage them from being matched to the original parent die. Finally, the eBay hoard that is currently the first recorded instance of these forgeries further helps in the case against them. We get an idea of how the coins are distributed to sellers and in what condition, and also how the suppliers of the sellers attempt to obfuscate and mislead their customers by supplementing fake coins with genuine coins of similar type and condition.

Hopefully this article serves as a proper documentation of these forgeries and somewhat of a guide in diagnosing them as forgeries. It’s almost certain that other examples of these forgeries but not the exact ones documented here will appear on the market and I would recommend vigilance when buying these types in the near future. Don’t just check to see whether the type and/or dies of a lion stater have been published here but whether they show similar flaws and mistakes that would point to them being of the same origin. It may be that forgers learn from their mistakes, hopefully in no part due to my analysis here, but I’m confident that due to reasons of economy and greed they will continue to make mistakes and a diligent collector or numismatist will still be able to spot them.

Bibliography

Hill, G. (1922). Catalogue of the Greek Coins in the British Museum: Arabia, Mesopotamia and Persia.

Houghton, A. and Lorber, C. (2002). Seleucid Coins A Comprehensive Catalogue. Part 1 Seleucus I to Antiochos III. New York/Lancaster, PA: American Numismatic Society and Classical Numismatic Group.

Iossif, P., & Lorber, C. (2007). Marduk and the Lion. In G. Moucharte (Ed.), Liber Amicorum Tony Hackens (pp. 345–363). Louvain-la-Neuve.

Newell, E. T. (1938). The Coinage of the Eastern Seleucid Mints: From Seleucus I to Antiochus III (Vol. 1).

Nicolet-Pierre, H. (1999). Argent et or frappés en Babylonie entre 331 et 311 ou de Mazdai à Séleucos. In Travaux de numismatique grecque offerts a Georges Le Rider (pp. 285–305).

Price, Martin J. (1991) – “Circulation at Babylon in 323 B.C.”, in W.E. Metcalf (ed.), Mnemata : papers in memory of Nancy M. Waggoner, New York, p. 63-72, pl. 15-17.

Stannard, C., & Fischer-Bossert, W. (2011). Dies, Hubs, Forgeries and the Athenian Decadrachm. Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau, 90, 5–32.

Stay up to date with the latest news from Artemis Collection by subscribing to the newsletter.